Cyber

Quantum

What does the UK’s Cyber Resilience Bill really mean for a quantum security future?

Reading time: 7 mins

Specialists in quantum technology are partnering with space experts to reach for the skies, but what is driving these collaborations? And what makes them the obvious next step for a better connected planet?

As if quantum technology wasn’t hard enough, why not try and put it in space as well? “Hard squared,” is how Boeing principal senior technical fellow Jay Lowell described the next phase of the company’s work on space-based quantum technologies to BI Foresight.

In fact, Lowell was referring to a very specific set of technical requirements on the road towards building a space-based network, one that can exchange information bearing the unequivocal hallmark of quantum mechanics – “entanglement”. It turns out that extraterrestrial orbits have been hosting quantum technologies for decades, including for everyday applications like navigation, where the stars that guided our ancestors have long been superseded by satellites exchanging signals timestamped with an accuracy beyond the scope of classical physics.

However, the past few years have seen a dial up in the ambitions harboured for the kinds of quantum technologies companies are looking to host from space. Trading in the consistency and control of lab conditions for the alien environment of space is no mean feat but, as far as the companies making a bid for it are concerned, the stakes are high and the pace is fast. The latest space race is on.

A key milestone in space-based quantum achievements was achieved in 2017 when scientists, led by Jian-Wei Pan at the University of Science and Technology in China, generated an entangled photon pair that was then beamed down to Earth from the Micius satellite. The experiment has been described as a “Sputnik” moment both in the press and academic circles, likening it to Russia’s successful launch of the first manmade satellite into orbit during the original space race. Not only was the Micius experiment difficult to achieve, but it inched the world closer to enabling a certain kind of quantum cryptography, with global coverage.

According to quantum mechanics, the properties of a quantum particle, such as a photon, can be in superposition, having more than one value – both horizontal and vertical polarisation, for example – until they are measured. Entangled quantum particles share a quantum state, so that while each may be in a superposition of states, once the value is measured for one particle the value of the other instantly takes on a specific known value however far away it might be – something Einstein notoriously described as “spooky action at a distance”.

Thus, distributing entangled photon pairs is a means of distributing a key between two people that no one else is privy to, and what is more the presence of anyone attempting to eavesdrop would be heralded by the collapse of the quantum states into specific values. As such the Micius experiment demonstrated an important capability for “quantum key distribution” (QKD) that prompted increased investment in quantum technologies from governments around the world, although not always with as much emphasis on enabling them in space as some would like, and with none plugging in quite as much as China.

For several decades now, QKD has attracted interest as a means of secure information exchange – one that does not rely on the traditional cryptographic algorithmic codes a fully-fledged quantum computer might easily crack. Various teams have advanced the technology since its proposal in the 1980s, including researchers led by John Rarity at the University of Bristol, who demonstrated entanglement- based QKD over several km of optical fibre. Fibre networks for quantum information spanning Bristol and Cambridge are also underway in collaboration with Toshiba and ID Quantique. However, exploiting satellite communication with such a quantum network could enable wider coverage.

A number of commercial players have weighed in. A consortium initially led by UK-based Arqit Ltd, now led by Honeywell, had aimed to launch the world’s first commercial QKD satellite constellation, with the first satellite built under a contract with the European Space Agency (ESA). Meanwhile in Luxembourg SES has led a consortium with a similar agenda.

However, as Rarity himself added at a press conference awarding him the 2024 Micius Prize, so far the infrastructure for QKD to be really useful is lacking. Furthermore, an analysis of QKD by the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) highlighted other limitations. Since QKD remains “vulnerable to physical man-in-the-middle attacks in which an adversary can agree individual shared secret keys with two parties who believe they are communicating with each other”, an accompanying authentication process would be required. The report also points out the progress of work standardising quantum-safe cryptographic algorithms, which would be free from QKD’s hardware and authentication requirements.

Nonetheless, a lot of companies pursuing prospects of satellites exchanging quantum information are not just thinking of QKD. Lowell explains that a quantum entanglement network could enable sensors and quantum computers that are linked up through entanglement. “That capability is much more powerful than simply a QKD network but is also much more difficult to deliver,” he adds.

In space, temperatures can vary rapidly over many tens of degrees, in stark contrast with the strictly regulated temperatures in the labs where quantum research and development generally take place. Extensive studies and tests are needed to understand and mitigate the effects of large temperature variations, as well as the significantly higher exposure to radiation. There are also more banal practicalities, such as launch, size, and weight constraints, and the need for remote operation and maintenance.

Boeing is ripe for the challenge. “If you really look at what Boeing does, its mission is to bring people closer together,” says Lowell. In the past that has meant flying people around the world and building satellites for worldwide communication networks. However, as quantum devices loom ever more imminently on the horizon, the need to connect these too is inevitable. “We need to have an understanding of how those quantum networking technologies will impact that business, because the alignment is so core to who we are as a company.”

“If you really look at what Boeing does, its mission is to bring people closer together”

Jay Lowell, Boeing

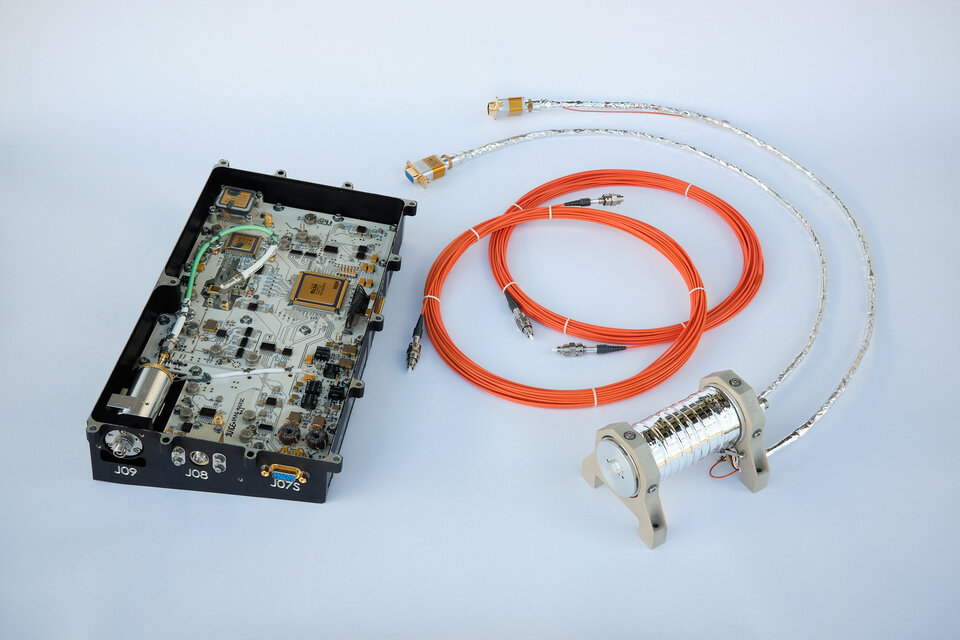

Three years ago, Lowell sat down with some colleagues at Boeing and “sketched out a basic experimental design” that would bring them closer to a quantum network in space. So far that design has survived with surprisingly few modifications, because despite the pace of progress in quantum technologies, the available resources that can meet the additional requirements of a project in space have not changed much. Towards the end of 2024, Boeing helped extend a project by researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to not just produce and detect entangled photons in space but also test how the devices respond and “self-heal” from radiation exposure through a process called annealing. The Space Entanglement and Annealing Quantum Experiment (SEAQUE) was a collaboration between the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the University of Waterloo, the National University of Singapore, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Glenn Research Centre, and optical technologies company AdVR, Inc, and in December 2024, the team reported successful measurements of Bell’s inequality – a test for entanglement.

For Boeing the next stage is to figure out how to exchange entangled photons between two satellites. Lowell explains that the fundamental challenge there is the need for very high-quality individual pairs of entangled photons, so that they can manage the interaction of one from each pair, and ensure entanglement, “so that we are actually performing a swapping operation that is maintained between the two satellites.” One big complication is that the clocks on the different satellites keep different times due to a general relativistic effect resulting from their different altitudes, but the team also expect to encounter a heap of smaller knotty issues on the way as well. Nonetheless they are confident they are on track, with Q4S due to launch in 2026 to demonstrate the next stage of producing and detecting multiple photon pairs. At that point Lowell believes the difficulty of moving forward with the project should begin to plateau.

Novel as quantum space tech sounds, there is at least one veteran among the suite of space technologies that is already fundamentally quantum. Atomic clocks hinge on the characteristic that gives quantum physics its name – the discrete packets or quanta that energy is traded in at that scale. The shorter the wavelength and higher the frequency of a photon’s wavelength, the more energy it has. As such the size of these packets of energy can be used as a measure of time. Atomic clocks are based on the quantum-sized differences between energy levels in an atom, providing a measure of time so accurate it has been used to define the second. For decades GPS has used atomic clocks on board satellites to triangulate the difference in travel time for signals sent from three satellites.

Various countries and diplomatic entities – the US, Europe, China, and Russia – have their own suites of satellites for their own GPS systems, and most phones will be able to receive signals from more than one. However, as the head of the opto-electronics section at the European Space Agency Eric Wille points out, the atomic clocks used for GPS need to be fully functional on, in the case of the ESA GPS suite Galileo, 28 satellites simultaneously, so the atomic clock technology used needs to be “mature and operational”. Such clocks may maintain an accuracy of nanoseconds but a record-breaking accuracy of 8 x 10-19 (8 tenths of a billionth of a nanosecond) was reported last year using a collection of strontium atoms in a lab.

Plans have been mooted to use some form of higher accuracy atomic clocks in space, where they would not be subject to gravitational effects such as vibrations or underground water flows. These could be used to test fundamental theories like relativity, provide an even more accurate definition of the second or serve as a master clock in an alternative global navigation satellite system architecture.

Sensors are another area where quantum effects can be exploited, from the properties of crystal defects to the shuttling of “matter waves”. However, where traditional sensors already exist, a possible quantum device needs to demonstrate its advantage. One type of quantum magnetometer that currently has an opportunity to prove itself is based on the effect of magnetic fields on the energy levels an electron occupies when it absorbs energy – the “Zeeman effect”. A magnetometer based on this effect, developed by Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) in partnership with Graz University of Technology, Austria, is currently on board JUICE, a spacecraft with a mission to explore Jupiter’s icy moons, where some expect to detect further evidence of promising environments for extraterrestrial life.

Interferometry offers another type of quantum sensor. It traditionally splits a beam of light, sends it around a circuit with mirrors and recombines it such that any difference in the path length for each part of the split beam becomes apparent when the peaks of the wave of light are shown to no longer match – an “interference pattern”.

According to quantum mechanics, matter can behave as waves too, so the same effect is apparent in a beam of atoms, but here electric, magnetic, and even gravitational fields will affect their journey in the interferometer. “In space, such interferometers can acquire even greater sensitivity owing to the long interrogation times that can be achieved in a freely falling instrument and the radically longer propagation distances that can be achieved, for example, in the open vacuum of space,” explained Dan Stamper-Kurn and colleagues at the University of California in Berkeley in their topical report Quantum Technologies In Space, which aimed to prompt more investment in quantum technologies specifically in space.

It is the potential for these interferometers to measure gravity that is attracting particularly keen interest at present. “You want to have a good view of gravity, because it gives you scientifically important values for understanding our planet, for climate models,” says Wille. Future applications that may even stretch to mining, and gas or oil field explorations, have also been suggested, although Wille adds that “these are quite demanding and it is not yet clear if future space-based interferometers can have a sufficient performance for these different applications.”

Nonetheless companies are now commercialising and shrinking interferometers, improving prospects of them on expeditions and even in space, something that various space agencies are following with interest. The European Commission currently has a project, CARIOQA-PMP (Cold Atom Rubidium Interferometer in Orbit for Quantum Accelerometery – Pathfinder Mission Preparation) underway, and NASA has a similar project in progress on the International Space Station.

“They are demonstrating the technology in orbit as a first important stepping stone,” says Wille. “Follow-on missions with increased performance will then be needed to address specific applications or science questions.”

There are even companies with their sights set on the possibility of hosting a functioning quantum computer in space. Quantum computers have the potential to be far more powerful than a classical computer by virtue of the fact that quantum bits – qubits – can exist in two states simultaneously, exponentially expanding their processing capabilities with each additional qubit. Although a quantum computing device that demonstrates a convincing useful advantage over classical machines remains agonisingly close but stubbornly beyond grasp, governments continue to invest billions in research, convinced of this revolutionary technology’s transformative potential.

However, as Roberto Siagri, entrepreneur and co-founder of quantum computing start-up Rotonium, puts it, “Qubits are incredibly delicate – like shy performers, they maintain their quantum properties only when completely isolated from outside disturbances.”

As a result, traditional matter-based qubits demand an extensive entourage of ancillary equipment, such as cryogenic or laser cooling, ultra-high vacuum and noise-shielding systems – creating a large, heavy, and complex payload that makes space deployment particularly challenging. Not only that, but most quantum computing architectures co-opt qubits for error correction algorithms to mitigate for the fragility of qubit states, leaving fewer available for computing.

Rotonium is developing quantum computers based on light that it believes minimise these challenges to a degree that could even make its computers viable for space missions. Key to this is harnessing a quantum attribute known as orbital angular momentum to encode additional information in its qubits, by enabling more quantum states in fewer qubits.

Furthermore, its approach to fault tolerance is through repetition of operations, allowing all qubits to be used for computation rather than dedicating many of them to error correction. This, combined with the photonic architecture that eliminates the need for cryogenic systems, results in a more efficient and less complex quantum computer. The net result is a quantum computing unit that is not just lighter in terms of payload, but also smaller, which reduces its radiation exposure.

“If you look in the direction of miniaturisation of edge photonic quantum computers with dozens of qubits,” says Siagri, referring to computation that happens at the “edge” of a network, enabling more resilient infrastructures that are less dependent on the centre, “automatically a lot of things solve themselves, though careful optical engineering is still required.”

There is another aspect to work at Rotonium that may explain what makes the company such a persuasive proposal to investors, and that is the choice of algorithms it is looking into. Siagri describes how, since noise can cause issues, the team have chosen to focus on algorithms that only require dozens of qubits, including AI algorithms such as pattern recognition where a little noise is “not so dramatic” and can be managed. This provides problems where using qubits enables, if not necessarily “supremacy” – by which people often refer to problems that only quantum computers can solve – then at least “quantum industrial utility”. In pattern recognition, the problem can be decomposed in a way that makes it manageable with a limited number of qubits, as is the case with many other practical applications.

“The point is just to do something practical that can be helpful in some business case at the cutting edge,” says Siagri.

Rotonium is not a space company, so it would require a partner with the necessary space expertise to turn the potential of its quantum computers to operate in space into a reality. The same goes for most quantum space technologies.

“Usually you need a good collaboration between a space company and a quantum company, because you need both experiences to make things work in space,” says Wille. With such collaborations in place, the sky is no longer the limit.

Anna Demming loves all science generally, but particularly materials science and physics, such as quantum physics and condensed matter. She began her editorial career working for Nature Publishing Group in Tokyo in 2006, and has since worked within editorial teams at IOP Publishing, and New Scientist. She is a contributor to The Guardian/Observer, New Scientist, Scientific American, Chemistry World and Physics World.

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Future Telecoms

Reading time: 2 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 11 mins

Robotics

Reading time: 1 mins