Artificial Intelligence

Materials

Net zero

Five energy technologies to watch in 2026 as the UK’s flexibility challenge comes into focus

Reading time: 5 mins

A look at how innovations in quantum, AI, semiconductors, and materials are starting to intersect

Back in October, OECD’s Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2025 reported that the convergence of technologies such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and quantum computing (among others) is increasingly shaping innovation, influencing not just products and applications but production methods and industrial organisation.

The report also claimed that this convergence is one of the reasons existing policy and funding frameworks are coming under pressure, as integrated technology pathways increasingly cut across traditional scientific, sectoral, and regulatory boundaries.

At the same time, each of these technology areas is advancing on its own terms. AI continues to scale through larger models, more specialised accelerators, and increasingly energy-constrained infrastructure. Quantum technologies are progressing unevenly but steadily across sensing, communications, and computing, with practical gains appearing first in niche applications rather than general-purpose systems. Meanwhile semiconductor development is being pulled in multiple directions at once, from advanced logic and memory for AI workloads to power electronics for energy, transport, and defence.

None of this progress depends on convergence in the short term. What could shape 2026, however, is the extent to which these advances begin to reinforce one another, as the OECD suggested, through shared infrastructure, hybrid workflows, and tighter links between hardware, software, and applications. That shift is already shaping how people working across investment and infrastructure are describing what comes next.

For Ion Hauer, principal at APEX Ventures, this marks “the definitive end of the ‘physics experiment’ era for quantum venture capital,” for example. Capital, he argues, is moving away from isolated breakthroughs and towards the engineering layers required to make systems usable together. “We are no longer looking for the next platform play,” Hauer says, “but for the interconnects and enablers, the unsexy but critical middleware, control electronics, and error-correction layers that make these massive systems actually work.”

That perspective places integration, rather than novelty, at the centre of investment decisions. It also reflects a broader expectation that quantum technologies will increasingly need to sit alongside classical high-performance computing and AI workflows, rather than compete with them. As Hauer puts it, “the Series A cliff will be steep” for companies unable to demonstrate a credible path to fault tolerance or integration with existing compute environments.

A similar emphasis on combination rather than isolation is emerging on the infrastructure side. In the UK, Isambard-AI entered full production in August 2025 and has since been taken up across a wide range of research domains. According to Simon McIntosh-Smith, director of the Bristol Centre for Supercomputing at the University of Bristol and responsible for Isambard-AI, the system “underpins most of the large-scale AI research in the UK today”.

Looking ahead, McIntosh-Smith says the interest is increasingly in how those AI projects connect to other forms of computation. “In 2026, we expect to see this continue and increase,” he says, “with results starting to emerge from the early adopters of Isambard-AI, and then for this to scale out as more and more AI projects come to fruition.” In practice, that often means AI being used alongside simulation, modelling, and data-intensive workflows, rather than as a standalone capability.

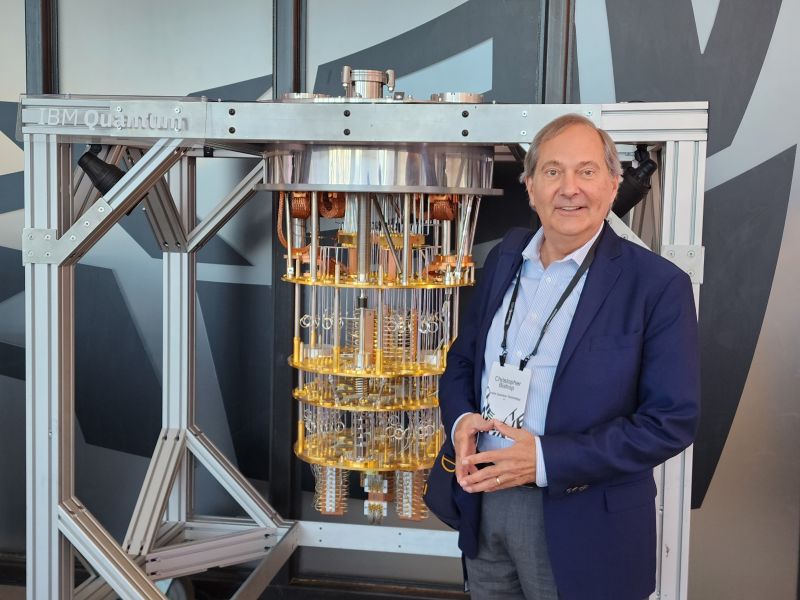

That same logic is beginning to surface in how quantum technologies are being discussed outside traditional research settings. For Christopher Bishop, a quantum industry evangelist and podcast host, one of the most telling moments of 2025 came from seeing quantum framed as part of a wider systems problem rather than as a standalone capability.

Reflecting on his role as MC of the Quantum Maritime Conference in Abu Dhabi last October, Bishop points to the way shipping executives approached the technology. “For two days, thought leaders in the shipping business discussed the tremendous potential of quantum-based technologies, from providing fast, immutable communication to improving logistics tied to scheduling and fuel consumption to manipulating fluid dynamics for ship design,” he says. “Exciting applications in an unlikely vertical.”

What stood out was not a single breakthrough, but how quantum was being considered alongside communications, optimisation, and modelling tools already in use. In that sense, maritime was less an outlier than an early example of how quantum is likely to be adopted, embedded within existing operational and digital frameworks, rather than deployed on its own.

Looking ahead to 2026, Bishop sees quantum sensing as the area where this kind of integration is advancing most quickly.

“Tremendous progress is being made in quantum sensors in biomedical, metrology, and geophysical applications,” he says. “Quantum-based magnetometry is poised to totally redefine navigation in settings where GPS is denied, jammed, or spoofed.” In healthcare, he adds, the gains are already measurable, with “quantum MEG devices detecting childhood epilepsy with 50x greater accuracy than existing systems”.

At the other end of the stack, convergence is also reshaping how enabling technologies are viewed. Rupert Baines, serial entrepreneur and non-executive director at the Compound Semiconductor Applications (CSA) Catapult, notes that semiconductors are once again attracting sustained political and industrial attention. “Semiconductors are fashionable in a way they have not been for 40 years,” he says.

That attention, Baines argues, reflects the way multiple technology agendas are now pulling on the same underlying capabilities.

“A lot of that comes from AI and AI-adjacent areas such as memory, networking, and interconnects,” he says, “but also things like power electronics for automotive, net zero, and defence.”

While he acknowledges that investment has not yet fully matched the level of interest, Baines adds, “I think 2026 will be better.”

Taken together, these ideas suggest that convergence is about increased dependencies. AI, quantum, sensing, and semiconductors are each progressing in their own directions, but increasingly they are doing so within shared infrastructures, supply chains, and application contexts. As the OECD noted, that creates pressure for policy and funding frameworks but it also opens up new pathways for collaboration, particularly where advances in one domain begin to unlock progress in another.

Working as a technology journalist and writer since 1989, Marc has written for a wide range of titles on technology, business, education, politics and sustainability, with work appearing in The Guardian, The Register, New Statesman, Computer Weekly and many more.

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Future Telecoms

Reading time: 2 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 11 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 5 mins