Artificial Intelligence

Materials

Quantum

Scaling Britain: why infrastructure is key to realising spinout potential

Reading time: 5 mins

From cyborg cockroaches to spider-like bricklayers, 2025 saw a strange mix of robot creations – but the real progress was in humanoids and industrial development

Robotics rarely has a quiet year, and 2025 didn’t disappoint. Cyborg cockroaches navigating rubble; drone swarms performing coordinated aerial manoeuvres that looked uncomfortably like murmuring starlings; and soft robotic tentacles inspired by octopuses handling delicate marine life with a gentleness that would shame most divers. Then there were the humanoids, jogging through warehouses, lifting boxes with surprising competence, and generally behaving as though they are ready to move into the real world (ignoring Russia’s glitchy AIDOL robot falling over on debut of course).

And at the more speculative end, a spider-like construction robot demonstrated how autonomous 3D printing could one day build structures on Earth or assemble habitats on the Moon. It’s been entertaining, occasionally unsettling but undeniably impressive. And yet the real story of robotics in 2025 lies not in the oddities but in the shift towards systems thinking, the rise of foundational AI models and the steady creep of automation into industrial environments.

See our infographic Robotics in 2025: from warehouse floors to operating theatres and humanoids for some stand out statistics.

What will all of this mean for 2026?

Almost certainly increased trials in industrial settings. How robots are integrated into real workflows, how reliably they operate, and how businesses, workers, and regulators adapt to machines that are now colleagues, will define the year.

Humanoids absorbed more media attention than any other robotics category this year, but gone were the endless backflips and dancing mascots. In their place came controlled pilots with automotive manufacturers, logistics companies, and advanced manufacturing sites.

BMW’s decision to bring Figure’s humanoid robots into its production facility in South Carolina is one of the clearest examples yet, with the robots being trained to handle line-side material movement, parts delivery and other high-churn, low-appeal tasks. GXO Logistics is taking a similar approach, deploying Agility Robotics’ Digit to manage tote-handling and warehouse replenishment cycles that suffer from chronic vacancies and rapid turnover.

Swarm robotics was a standout in 2025. As we reported in There’s a swarm coming: how robots are learning to solve human problems, researchers at Bristol and Windracers demonstrated coordinated drone fleets capable of covering vast wildfire zones, mapping dangerous terrain, and responding to rapidly shifting conditions without a human pilot for every unit. These showed how distributed robots can outperform traditional, centralised systems when environments are unpredictable or hostile.

Soft robotics made similar strides, albeit in very different settings. In Soft robots, hard truths… Can the UK deliver on robotics vision? we highlighted how octopus-inspired underwater manipulators and compliant medical actuators are enabling robots to work delicately with coral, tissue, and fragile assets that rigid machines routinely damage. These technologies are beginning to unlock new markets, from subsea inspection to minimally invasive surgery, precisely because they solve problems traditional robotics can’t.

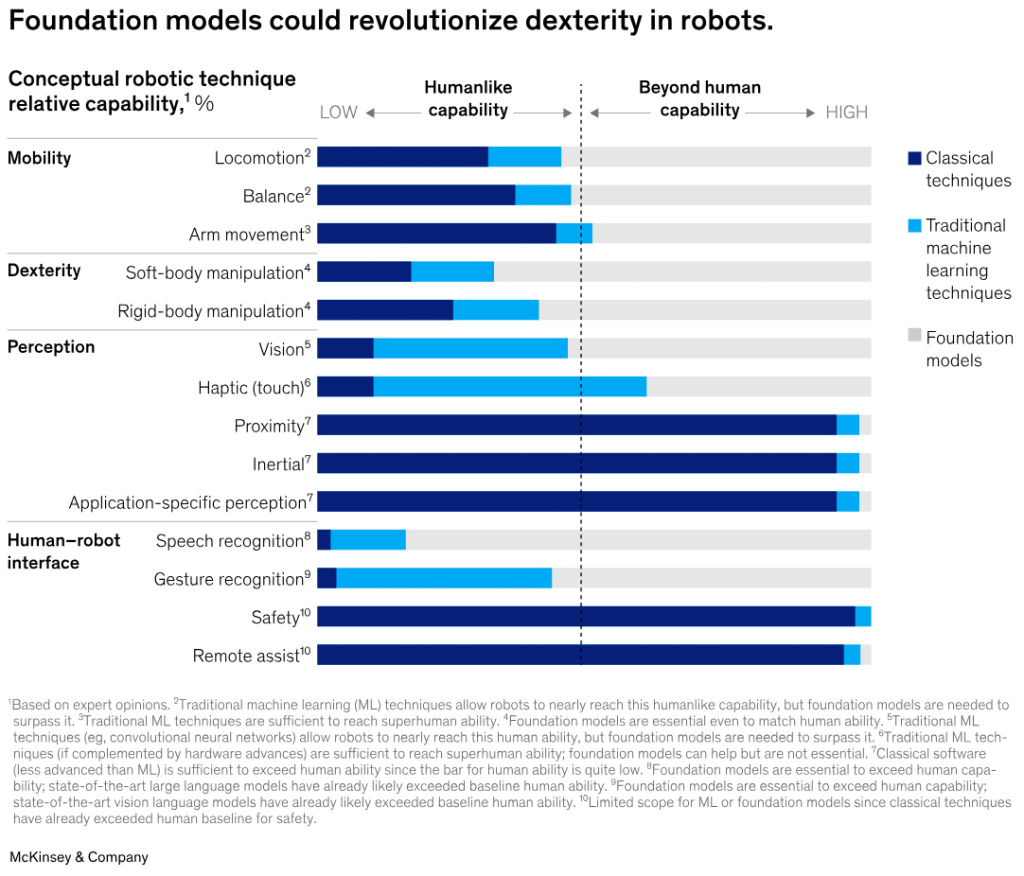

Another major development this year was the arrival of foundation models in robotics. As McKinsey has pointed out, the sector is moving away from single-purpose machines towards general-purpose systems that can adapt to multiple tasks. Foundation models make that possible. Instead of training a robot separately for every behaviour, you give it a broad base of vision, language and motor understanding that can be fine-tuned on the job. A command like “pick up the red mug and put it on the table” becomes a single instruction, not a carefully scripted sequence of movements.

This is important because it is adding “intelligence” to dexterity. Classical control techniques have kept robots stable; traditional machine-learning has helped them walk and grasp; but multimodal foundation models allow them to reason about what they see and hear, and then act on it. It is the difference between automation and collaboration.

The World Economic Forum has reached a similar conclusion in its recent Physical AI report, arguing that robotics is entering a new phase where machines combine perception, reasoning, and motor capability into a single system. Instead of automating narrowly defined tasks, robots become platforms that can adjust to changing environments, collaborate with humans, and take on work that previously required constant supervision. It is, in effect, the operational expression of foundation models, intelligence embodied in physical systems.

As 2026 begins, the most significant shift is in this intelligence behind robotics. McKinsey argues that foundational models could push robotics from narrowly programmed machines toward general-purpose systems that can perceive, reason and act across many different tasks. Instead of scripting every movement, robots gain a shared base of vision, language, and motor understanding they can adapt on the fly, a change that could make automation far more flexible and collaborative.

The promise is huge, but so are the caveats – reliable perception, energy limits, safety, and the hard graft of integrating these systems into real workplaces. The coming year will test whether foundational models genuinely unlock a new class of adaptable robots, or whether the technology still has a long road to travel from impressive demos to dependable infrastructure.

For all the technical progress, the real constraint going into 2026 is people. Industries that once needed a handful of automation engineers now rely on teams of roboticists, integrators, safety specialists, and technicians just to keep systems running. Yet the supply of talent has not kept pace. Manufacturers, hospitals, logistics providers, and public services all report the same problem. They can buy the robots, but they struggle to find the skills to deploy, maintain, and govern them. In the UK especially, shortages in mechatronics, embedded systems, automation engineering, and AI operations risk slowing adoption just as demand accelerates. The skills gap is real, but also one of the clearest areas where targeted investment can have an immediate impact. With coordinated training, apprenticeships and industry–university partnerships, the UK can turn a constraint into a competitive advantage.

As we argued, the UK has world-class research in areas such as soft robotics, autonomy, and swarm systems but struggles to turn breakthroughs into scale. Testbeds are fragmented, procurement pathways are slow, and companies developing genuinely novel systems often find themselves without the patient capital or long-term support needed to commercialise hardware. Other regions, from South Korea to the US, are moving faster by making robotics a pillar of industrial policy, tying research funding to deployment, and supporting early adoption in public services.

A coherent strategy matters because investment alone won’t close the gap. The UK’s £13.9bn public R&D commitment in 2025 – including £2bn for AI and automation, £400m for defence robotics and a £30m spinout support fund – is significant, but without the workforce to absorb it, much of that value risks stalling. Robotics is no longer constrained by ideas. The countries that pull ahead in 2026 will be those that align funding, skills, and deployment into a single pipeline, turning research strength into real-world capability rather than letting breakthroughs slip into the usual valley between invention and adoption.

Taken together, these trends point to a clear direction for 2026 that will be defined less by attention-grabbing prototypes and more by bigger questions around co-working with robots, as well as reliability and trust in robot systems.

Physical AI, as Gartner predicts, will be a key development in 2026. “Physical AI brings intelligence into the real world by powering machines and devices that sense, decide, and act, such as robots, drones, and smart equipment,” the company writes. “As adoption grows, organisations need new skills that bridge IT, operations, and engineering. This shift creates opportunities for upskilling and collaboration but may also raise job concerns and require careful change management.”

It all points towards another rapidly developing year for robotics. Innovation will still play a huge role, but the industry has matured to a point at which other factors come into play. How organisations and businesses manage scale, finance, skills, and regulation, for example, will be a determining factor this year. If 2025 showed us the art of the possible, 2026 will reveal who can turn possibility into practice.

Working as a technology journalist and writer since 1989, Marc has written for a wide range of titles on technology, business, education, politics and sustainability, with work appearing in The Guardian, The Register, New Statesman, Computer Weekly and many more.

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Future Telecoms

Reading time: 2 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 11 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 5 mins