Artificial Intelligence

Cyber

Future Telecoms

Materials

Quantum

Wise words and waggishness… February 2026

Reading time: 2 mins

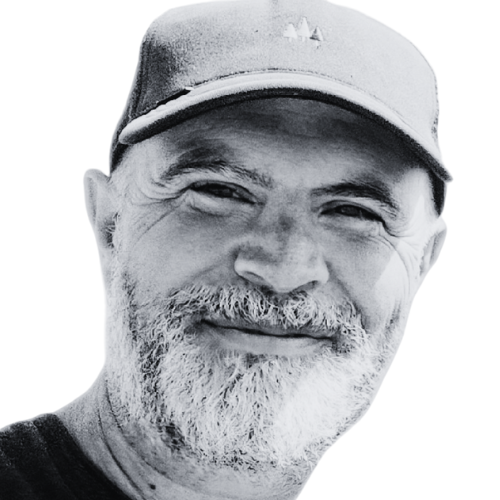

Currently valued at $3bn, PsiQuantum is pushing the boundaries of science. We talk to the company’s co-founder Dr Pete Shadbolt.

Pete Shadbolt is co-founder and chief scientific officer at PsiQuantum. Established in Bristol in 2016, PsiQuantum is currently valued at $3bn, and was created with a simple but sublime mission: to build the world’s first commercially useful quantum computer based on silicon photonic technology.

After completing his undergraduate degree at Leeds University, Shadbolt moved to the University of Bristol, where he earned his PhD in experimental photonic quantum computing in 2014, demonstrating the first-ever Variational Quantum Eigensolver, as well as developing the first public API to a quantum processor.

Following his PhD, Shadbolt completed a postdoc at Imperial College London, researching the theory of photonic quantum computing. And in 2016 he co-founded PsiQuantum – now based in Palo Alto, California – alongside fellow scientists Jeremy O’Brien, Terry Rudolph, and Mark Thompson.

In this exclusive Foresight Q&A, we discuss how Shadbolt transitioned from award-winning academic to startup co-founder; discover where he sees quantum technology advancing to within the next decade; and learn how his love of video games sparked a lifelong passion for mathematics.

A: It was essentially under duress. It was the 90s, and I asked my mum and dad for a Nintendo. And they said, “No. You can have a 486 desktop IBM and a copy of Turbo Pascal. And then you can make your own bloody video games.” And that was how it all began.

A: I grew up in Oxfordshire, and was lucky to have a family friend that got me a copy of Turbo Pascal when I was younger. And I learned to program computers because I wanted to make video games. As a result of that I understood some vector arithmetic and stuff like that, basic mathematics, and then got into physics. Then I went off to Leeds University and did my undergraduate there.

A: There was a group in the experimental labs in Leeds, where I got to tinker around a little bit. And then I went off to the University of Bristol to do my PhD. I’d come to the conclusion that quantum computing was the most interesting thing I could do with my life. And when I asked around about who in the UK was doing quantum computing, someone put me in touch with Jeremy O’Brien. Jeremy is now our CEO at PSiQuantum. He’s originally from Australia, but had moved to Bristol to start a quantum research group. I was really just in the right place at the right time.

A: It turns out that you can make chips where what moves around on the chip is light, instead of electricity. This is photonics. It was originally developed by the telecoms industry for networking. And Jeremy and the early members of their research group decided they were going to repurpose that technology, and use it to try and put single photons in a computer chip.

A: That research group just took off like a rocketship. And I was very lucky to join around that time, when they were making the first set of chips. The Bristol research group was where a lot of the first quantum demonstrations happened. It was the first time qubits were put on a chip; the first time we showed logic and gate operations between qubits; the first time we did algorithms to calculate things with tiny, quantum processors. And I just had a wonderful time.

A: There are hubs for quantum computing around the world. But the really good people in quantum computing, more often than not, come from a few places. And why is that? Well, I think it’s because certain countries took quantum computing really seriously 20 to 30 years ago. Predominantly Australia, the UK, the US. So when I rocked up in Bristol, there were already vibration isolated labs and laser systems, and a community of people who knew the ground rules of quantum information. That was really important.

A: One of the defining characteristics of PsiQuantum is that we are absolutely pig-headed in only targeting large-scale, fault-tolerant systems. We believe that this organisational focus is necessary in order to have a chance of crossing the scaling gap in short order. However, sometimes it is understandably inferred that our roadmap is “zero-to-one”, with no intermediate milestones. Of course, we have many intermediate milestones and have demonstrated systems, manufacturing processes, and proof points which represent profound de-risking of the path to a full-scale quantum computer. The big difference is that we do not claim that these prototypes are small quantum computers, and we do not attempt to operate them as such.

A: A simple way to understand this is that instead of flying toy rockets with solid rocket boosters (SRBs) in our backyard, we are investing in an orbital rocket engine with a hundred tonnes of thrust. Today our rocket engine doesn’t lift off, but we judge that this is a better use of funds.

A: People who invest in quantum computing, generally speaking, are hoping that the sector will soon become as significant a technology as conventional computing, artificial intelligence, the internet, nuclear power or semiconductor manufacturing. In other words, a load-bearing component of our advanced society with huge strategic and financial value.

A: We talked to a lot of investors when we were raising early funds for the company (A and B funding). And our story was highly unpopular with a large number of them. So we disqualified ourselves with investors who couldn’t stomach the real thing. But we were very lucky to find a few investors who understood that what we were saying was true. It was necessary to be a little bit deranged, and explain to investors that, for a useful quantum computer, you didn’t need tens or hundreds of qubits – you needed a million qubits. We’re going to build a million-qubit quantum computer. That’s the plan.

A: The majority of our technical team are electrical engineers and semiconductor people, without a quantum computing background. In contrast, the most acute and under-resourced recruiting areas are the esoteric domains of quantum architecture, fault-tolerance, error correction, and development of quantum algorithms. Progress in these areas is really only made by mathematically gifted, technically very deep people with postgraduate-level expertise in quantum information. In this sense, quantum computing can be compared to AI – the hardware is delivered by electrical engineers, whereas the algorithms are produced by rare and mathematically elite PhDs.

A: Many teams are now starting to talk about fault-tolerant systems within the decade. While these roadmaps should be understood as being very optimistic, we think this is a healthy target for the industry.

A: The really exciting area to focus on over the next several years is going to be fault-tolerant quantum algorithms. While we’ve had algorithms developed for smaller quantum computers, a utility-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computer will require entirely new algorithms. However, these will be some of the first algorithms to have potentially incredible impacts in the worlds of materials science, pharmaceuticals, and the energy transition.

Dan Oliver is a UK-based technology and design journalist with 25 years of experience. Dan has produced content for numerous brands and publications including The Sunday Times, TechRadar, Wallpaper* magazine, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and more.

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 10 mins

Future Telecoms

Reading time: 2 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 11 mins

Quantum

Reading time: 5 mins